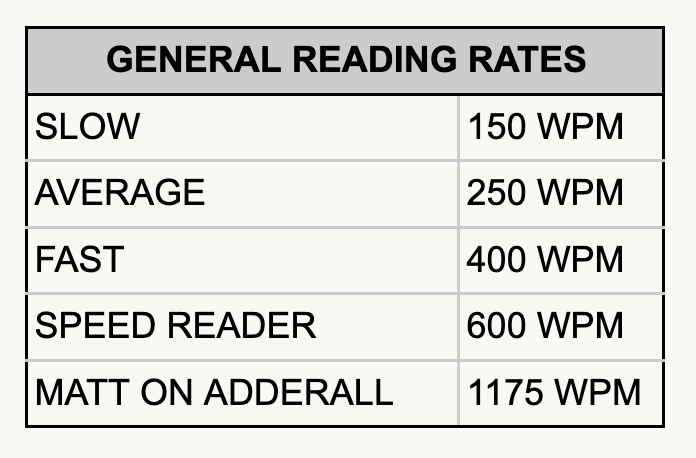

When I’m locked onto the page I read 270 words in a minute. Usually I’m not locked onto anything. Usually when I sit down to read, or do anything for that matter, my mind wanders immediately off into the wilderness—chasing whims around the internet, scrolling downward into bottomless feeds, adding to phantom to-do lists, re-organizing those to-do lists. Like just about everyone I know, I have an attention span that can only be measured theoretically. This state-of-mind is a matter of grave concern when you have an imminent deadline, and it is enough to put you flat on your back when there are 600 pages of nineteenth-century Russian Literature between you and that deadline. In spring semester, 2010, I found myself in such a situation. I needed a workaround.

Fortunately, I found one. With my deadline rapidly approaching, I read Crime and Punishment in three hours. I didn’t just read it either. I highlighted, dogeared, Post-It flagged, and compulsively highlighted all but a few of its 211,591 words. That’s 1,175 words per minute. I then wrote a 10-page essay without ever rising from my seat and I submitted it that evening. I received an A. I’d quintupled my processing power. What was my workaround? Amphetamines. Specifically Adderall, from a contraband bottle in my roommate’s sock drawer.

That happened on a Friday. Over the weekend I wasn’t thinking about Raskolnikov and I wasn’t playing beer pong in North Quad. Instead I hiked up into the San Gabriel Mountains to look over the Mojave; to sit alone on a granite outcrop and think. Upon that rock under the white fir, I may have appeared grounded, but inwardly I was wobbling. For many years I’d struggled profoundly to focus, and now I had finally taken the focus pill and it was breathtaking. I had a choice to make. On the one hand, I could continue to accumulate books faster than I could read them; on the other, I could forever read them faster than I could buy them. It was a Faustian Bargain, except, instead of trading my soul for the world of knowledge, I’d have to accept side effects like occasional nausea, increased anxiety, irregular heart rate, and an unnerving reflex to clench my jaw, which I seemed to do relentlessly as I plowed through Dostoevsky.

As a scattered student, the promise of attention on-demand was seductive, but the clear mountain air above Icehouse Canyon must have talked me out of it. I decided then and there that I would never take Adderall again. It wasn’t the heart flutters that worried me (worrisome as they were), it was the inevitability of dependence. I knew I was no match for it. I’d taken just one pill, and I was already starting to feel an onset of addiction to focus. Already, I could hardly imagine reading another book, not to mention living, without it. This spooked me to my self-sufficient core. I’ve been Adderall-sober for fourteen years, but all the while I’ve been searching for another on-switch.

For fourteen years I’ve tried and failed to increase my attention span the natural way. It became something of a Sisyphean obsession. I experimented with sleep phasing, eastern pharmacology, ketogenesis, time-blocking, mantras, and focus balms. I used and still use an app called “Self Control” to hide a quarter of the internet from myself. I took artichoke extract in a capsule on and off for a year. I canceled my AT&T contract, sold my phone, and disappeared from the cellular grid for four months. I survived a bootcamp in Onalaska, Washington, where I meditated steadfastly from 4:30 to 17:30, without saying a single word over ten days. I’ve tried virtually everything to increase my attention span, but my progress soon relapses with each new iOS update or news headline. There is an adaptive difficulty to concentration. The opponents improve at a rate that is impossible to keep up with.

Meanwhile, as I’ve tried to cling to my last atomic particles of focus, the attention-span of the world around me has been clinically dismantled by a booming attention economy. A lot can happen in fourteen years. The attention that I was struggling so hard to pay in 2010, is now a blue chip commodity. Attention, my attention and your attention, is bought and sold by you-know-who: Apple, Facebook, Google, TikTok, Elon, CNN, Fox, NYT, et. al. You know who, because by this point Big Tech’s onslaught on our attention is a tired storyline. The world has moved on to the existential implications of artificial general intelligence. Focus, concentration, and the entire enterprise of voluntarily directed attention, have come to represent quaint relics of a bygone era. The days of focus are over now. Abandoned and outsourced to a GPT.

As our ability to concentrate has collapsed, I’ve become more and more convinced that it is the superpower we should long for. Sustained focus is the engine that connects dots and builds things. To concentrate with the intensity of a chess grandmaster on the object of your choosing is to find out what you are capable of—what you are capable of knowing, understanding, creating, and becoming. "The concentration is like breathing—you never think of it,” says one grandmaster, reflecting on a game of tournament chess, “The roof could fall in and, if it missed you, you would be unaware of it.”1 I hear this and wonder what my life might look like—what I might create and accomplish—if I could concentrate for just a few hours, let alone under a collapsing roof.

Besides the grandmasters, there are others who know the power of concentration. Concentration is how JavaScript was prototyped in 10 days. It’s what allowed Walt Disney to develop his eponymous land in 366 days. It’s what powered Mary Shelley, when she wrote the first draft of Frankenstein in just a few summer afternoons. It’s what Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid and inventor of consumer photography, credited for his legacy, when he said, “My whole life has been spent trying to teach people that intense concentration for hour after hour can bring out in people resources they didn't know they had.”

Above all else, blinders-on, self-directed focus is an essential ingredient on the path to personal fulfillment. Without it, you’re in the wilderness. It’s impossible to feel deeply fulfilled at work, in a relationship, in your one precious life, when your thumb twitches neverendingly towards red bubbles; when you have little control over what you spend your time thinking about.

A few months ago, my fourteen year concentration crusade reached a boiling point. After wholeheartedly committing myself to sit down and make headway on my next business, my effort came immediately to a screeching halt to make way for an urgent incoming thought: How is Beyonce’s country album doing? Is there an accent over the e in Beyonce? I Google her name. There is an accent. And the album broke the single day streaming record. Wow, she has 320M Instagram followers? That seems like a lot. Like, a lot a lot. Is that actually the most? Isn’t Taylor Swift way bigger than Beyoncé? Huh, Taylor Swift only has 283M followers. Hmm, so no bad blood. Is Beyoncé actually bigger than Taylor Swift? This must be measurable somehow. How? Wait, who actually has the most IG followers? Wait what. Cristiano Ronaldo has 627M IG followers!? That’s like 1 in 15 humans. Isn’t it? What’s the global population now? 8.1B. Wow, so yeah closer to 1 in 14. That’s wild. Almost 8% of the world follows a football player. Also damn. Instagram must have so many users. Wow, 2 Billion MAUs. And more than a quarter of them follow Cristiano Ronaldo. That’s an underratedly crazy fact. Does he even post interesting stuff? Scroll, scroll, scroll, tap. Scroll. Yeah no, not even a little bit. Imagine if he did...

I came back into consciousness and found that I was looking at @cristiano’s Instagram page. My attention span had hit rock bottom. My self-confidence, receding unfathomably with it, was somewhere in the Mariana Trench. It wasn’t the first time I’d returned from a dizzying tangent that day and it wouldn’t be the last. In fact, it was the kind of tangential tangle that my days seemed to be made entirely out of. From the deep I wondered, How in God's name am I going to build my next business if I can’t hold and control a linear thought for more than a few minutes? I had no control of my mind, and I quite simply couldn’t take it any more. I decided right then that I would make concentration my total obsession. I would stop short of nothing in pursuit of focus. I would join the grandmaster at his table, and I would learn to stare at a problem unblinkingly until it began to smoke.

That journey started four months ago now. At that point I had ADHD2. Now I don’t. Now I sit down to do something and I don’t get up until it’s done, and I don’t think about anything else but the thing I’m doing. Over the past four months I’ve read 10 books about concentration and I’ve read even more studies. I’ve devoured everything that I could find on the topic, and I’ve made my life into an immersive experiment. I’ve figured a lot of things out.

Most fundamentally, I’ve found that there are tactics for dealing with the external distractions, and there is applied theory for addressing the root causes of attentional failure. The root causes have to do with your brain, heart, and gut. Reconfiguring these things requires (very) hard work, but that’s how you fix your attention. Deleting Instagram is a tactic, (like so many of the things I tried over fourteen years). Delete it all you want, but the moment you re-download it (you will) you’ll find that your attention is as hopeless as ever. What you really want to do is fix the big problem at the bottom of the problems. You want to become totally undistractable, and to do that you need to address root causes. And unless you’re willing to make it your number one priority for several months, you will need help. I can help.

Having made astonishing progress myself, I’ve concluded that grandmaster-levels of concentration are attainable even for people with clinical levels of attention deficit. I don’t make that claim lightly, as someone who spent years trying and repeatedly failing to overcome chronic distractibility. I know that a leap like this is possible because I made the leap. At this very moment, I’m in the middle of doing something that I never would have dreamed possible a few months ago: I just wrote a draft of this essay in one sitting, over 3 hours, with no urgent deadline, while my wife moved ceaselessly around our old, rental mill house on creaky floors. This would have overwhelmed my old-self into an illiterate swivet. Now, I focus like this at will, everyday, whenever I want, for huge stretches at a time. Four months ago, a pin drop (real or imagined) was all it took to ruin a working session. Now it takes a SWAT team.

If I can do it, you can do it. It just takes a lot of well-designed effort.

It is a lot more difficult than popping amphetamines. It will take more than 10 minutes per day, and it will require more discipline than it takes to passively listen to Huberman Lab on your commute. The pursuit of ‘grandmaster-mode’ demands wholesale changes of diet, work habits, sleep schedule, fitness routines, communication style, and priorities.

If you’re interested in legitimately transforming your ability to concentrate, I’ve designed a program that is instructive, progressive, and effective. I’m sharing it because I looked everywhere and couldn’t find it in one place—every book I read, while helpful in some way, was missing crucial components of the solution that worked for me. And when I was at my low point I would have done and given just about anything for a credible guide that treated me like an adult.

Through a series of essays and a structured system for ‘training’ focus, I plan to create a different kind of focus pill. Fewer things could be more important than reclaiming control of the thing that controls—your mind, your focus. Your life.

Thanks to

for feedback on this essayExcerpted from Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

I seem to be constitutionally incapable of visiting a doctor, having avoided it entirely going on 10 years now, so I don’t have a doctor’s note to prove that I had ADHD. This of course means that haters will say I never had it. I regret having never been clinically tested because I suspect that I would have tested off the charts, which would have made my transformation more compelling to many people. At any rate, I’ve read enough about ADHD, its symptoms, and the methods of self-diagnosis to confidently say that I had it. And besides, ADHD is a clinical diagnosis, meaning it is observationally evaluated and diagnoses are being handed out more happily and haphazardly than the stimulus checks of 2020. Here is one trend line.

Such powerful, writing! Such a vital topic to explore! I gulped down the text, seeing so much of myself and our ‘focus less’ world being exposed . Focus failure. Yes!

I admire your thinking, your tenacity, your experimentation in the search for improvement.

‘Without it, you’re in the wilderness. It’s impossible to feel deeply fulfilled at work, in a relationship, in your one precious life.’ Yes!! Time to do something about it. Thank-you!

PS I love learning new words from you. ‘Swivet’. Cool!